Article from High Country News : Mexican Ranching

Feature story on Borderland Conservation

written by Tony Davis

photographed by RAEchel Running

At 6:30 on a warm spring morning, a brightly colored summer tanager flits above green cottonwood, willow and sycamore trees. Lower down in the forest, a vermillion flycatcher darts from one mesquite branch to another. A piercing cry — “ke-er” — draws attention to a gray hawk perched on a bare branch, and a Bell’s vireo inquires, “Cheedle-cheedle-cheedle-chee?” as it flies through the tree canopy. It’s a noisy avian symphony, underscored by rustling winds and the burble of a creek.This could be a scene on the banks of Arizona’s San Pedro River, where a federally protected United States conservation area has attracted hundreds of bird species, along with international recognition as one of the Southwest’s best remaining riparian riverfronts. But this birder’s paradise lies along Río Cocóspera, 30 miles south of the U.S.-Mexico border, in a private preserve in the Mexican state of Sonora.

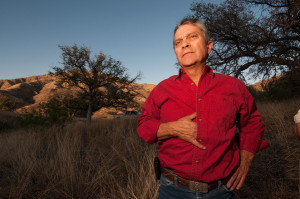

Landowner Carlos Robles Elías, a trim, 5-foot-6-inch 57-year-old, his black hair streaked with gray, expresses pride in the biodiversity found on his 10,000-acre portion of Rancho El Aribabi, which has been in his family for three generations. Much of it has been created by his own renegade ranching practices. For a decade, he’s whittled down the number of cattle he runs, to reduce grazing impacts, while building a new ecotourism business and selling trophy deer hunts. In a camouflage baseball cap and hiking boots instead of the usual cowboy outfit, he radiates seemingly endless energy as he drives a reporter around his spread during a two-day visit. Underneath a tree high in the Sierra Azul mountains, he reflects on the changes he’s made: “Before, it was just for making a living. … Now, I feel so good. I’m making a difference. Siento que soy alguien. I feel like I’m somebody.”

He stops to repair a damaged water tank, replacing a bent plastic pipe with a metal pipe. It’s part of a network of 32 small tanks and 20 miles of underground pipe he has installed to benefit cattle and wildlife on the ranch. But later, as he walks along a path beside the river, he turns and speaks candidly: “Please print that we need help.”

He needs help because he’s trying to be an agent of change and also make a living. Traditional cattle ranching has dominated Northwest Mexico since the 1600s. More than 80 percent of Sonora is grazed by livestock, and the ranching culture and economy are as entrenched here as they are in the rural Western U.S. Yet Robles is not entirely alone on his path toward reforming ranching: A few U.S. conservation groups have reached across the border to support restoration efforts on his and other Mexican ranches. Mexico’s government and some Mexican groups are also involved, in a trend that’s similar to but smaller than what’s happening on U.S. ranches. Mexico’s ranches are important to conservationists in both countries for many reasons, including the tremendous biodiversity of this part of Mexico and the crucial wildlife corridors that straddle the border.

Robles’ efforts have earned the admiration of many scientists and conservationists on both sides of the border. His ranch has become a symbol of hope in the midst of the region’s notorious troubles — the illegal traffic in undocumented immigrants and the terrible Mexican drug cartel violence that has killed nearly 50,000 people in the last five years. His stretch of Río Cocóspera holds one of the area’s few remaining intact marshy cienegas. Farther uphill, in the Sonoran and Chihuahuan desert uplands, waist-high grasses ripple, and there’s a jungle of blue oaks that tops out at 6,000 feet elevation. He’s providing habitat not only for the Coues white-tailed deer — much coveted by hunters — but also for jaguars, ocelots, coatimundi and dozens of other species that the Mexican government considers imperiled.

Last spring, when HCN visited the ranch, it looked wonderful. Robles had finally reduced his cattle from 1,100 head all the way down to zero — a key move, he believes, in restoring the land from previous abuses and keeping the ecosystem healthy. “I don’t like the way ranchers think,” he said — traditional ranchers, that is.

Robles, right, and Sergio Avila of Sky Island Alliance, use maps to plan restoration efforts.

Photo by Raechel Running

But Robles’ income from birdwatchers and hunters has declined drastically over the last few years, mainly because the much-publicized drug-cartel violence has discouraged potential customers. And he hasn’t been able to get as much help as he’d hoped for from conservation groups and agencies. So since last spring, he’s had to put about 1,000 cattle back on the land, to scratch out a modest income from beef production. Last October, he emailed that his long-term goal was still zero cattle, adding, “I feel bad, for sure, because I’m walking back.”

In broken English, Robles elaborated on the effects of reintroducing cattle, in another email a few weeks ago: “We are seeing so shorter grass … in the deeper or microscopic life (it) means a lot. … the health of the ecosystem will be decreasing slowly like a chronic sickness, and of course, erosion … the impact is (also) emotionally because I have a different vision …” His continuing struggle highlights both the good news about conservation in Mexico, and the unique and at times almost overwhelming difficulties.

Robles’ great-grandfather bought what is now Rancho El Aribabi in 1888, and generations of the family have remained connected to the land. Robles grew up in Nogales, a border town where his father ran restaurants, but he often visited the ranch. At a young age, he fell in love with cattle roundups and horseback riding. He was also fascinated by nature, collecting butterflies and bugs and devouring nature encyclopedias instead of the comic books his friends preferred. Even back then, he says, his family and other ranchers worried whether cattle were sustainable. The acreage grazed by livestock in Mexico soared 260 percent from 1950 to 1990, and, Robles recalls, “I would hear too many times from neighbors that they would bring in more cattle because the rain was big enough … but suddenly the rains stop. No rain, no grass. Then they would say, ‘What are we going to do?’ ”

One of his brothers, Eduardo Robles, says that early on, “a seed was planted in Carlos’ heart, this belief that something was not working well for nature. … He would talk about trees, grass, the environment. He liked being a cowboy, (but then) changed his mind and said, ‘We can put the ranch to other uses.’ ”

Robles moved out to the ranch when he was 27, with his wife and young son (they now have three kids), after studying agriculture at the University of Guadalajara. In 1987, he became the owner of his 10,000-acre portion. (Eduardo and a cousin also have 10,000 acres each.) He grew increasingly disenchanted with the impacts of grazing and recurring droughts. Even when ranching was profitable, he says, “You are only living the life of overgrazing.” In 1991, he sold his cattle and started leasing his land for other ranchers’ cattle, and in 2000, he began reducing the number of cattle in the leases — dropping to 150 by 2008, 50 in 2010, and briefly — in 2011 — hitting zero. (To supplement the family’s income, his wife runs a hotel in Magdalena, a 45-minute drive away, where Robles helps out when he has time.)

A U.S. conservationist encouraged Robles’ venture into conservation ranching. At a 2000 meeting in Hermosillo, the capital of Sonora, Tom Wood, co-director of the Southeastern Arizona Bird Observatory, a nonprofit group that aims to “conserve the region’s birdlife through research and public education,” sought to educate Sonora’s ranchers about the possibilities of ecotourism. None of the other ranchers were as intrigued as Robles, who came up to Wood afterward and asked, “How quickly can we do a bird inventory?”

Eduardo Limón, a freelance biologist and ornithologist in Hermosillo who also attended the meeting, visited the ranch soon afterward and was surprised by its good condition. Robles was already rotating cattle to keep any area from being grazed too long. That year, Robles also installed a couple of remote cameras on his ranch to photograph wildlife. Limón saw impressive habitat and counted about 140 bird species. He called the Sonoran Joint Venture, an organization of government agencies and nonprofits based in Tucson, whose mission is to conserve borderlands birds and their habitats. Since the Joint Venture shares an office building with the Tucson Audubon Society, word of mouth soon brought many U.S. birders to the ranch, along with a host of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service fish, bird, reptile and mammal specialists.

“I went down a couple of years later (during a dry spell) and the headwaters of the stream was bubbling up out of the ground, and the stream was flowing well,” says Wood, whose organization has sponsored eight ecotourism trips to Aribabi. “I was amazed.”

During the mid-2000s, the Joint Venture, which is staffed by wildlife service biologists and governed by a board of researchers, bureaucrats and conservationists, included Robles’ ranch in a study of important bird habitats. In 2003, it gave him a further boost by paying $30,000 to fence off Río Cocóspera from cattle. Even before that, Robles’ riverfront vegetation was in the best shape of the 20 areas studied, recalls Robert Mesta, the Joint Venture’s coordinator. “The other areas in Sonora that we studied were hammered. Other than large cottonwoods and willows, there was nothing left. His was still pretty lush … despite the fact that it had been grazed,” Mesta says.

Once the stream was fenced, the grasses and shrubs grew up to six feet high. The bird life increased to 180 species, says Limón, who conducted monthly surveys from 2000 to 2010. New arrivals included the summer tanager and the Sinaloan wren.

Robles had to jump through some hoops to get the Mexican government’s permission to sell deer hunts. There is virtually no government regulation of ranching in the country, but Robles was an early participant in an innovative Mexican conservation program: Unidades para la Conservación, Manejo y Aprovechamiento Sustentable de la Vida Silvestre, better known as the UMA program. Created in the 1990s, it encourages ranchers to work with biologists to create plans for managing wildlife in sustainable ways that also make a profit, such as selling hunting opportunities. (Since the UMA program began, hunting is legal only on UMAs.) Robles won approval as an UMA in 1998 and began selling hunts.

Robles also benefitted from an extraordinary relationship with the Sky Island Alliance, a Tucson group that seeks to restore and protect the biodiversity of mountain ranges on both sides of the border. It began when a Sky Island Alliance biologist, Sergio Avila, came to the ranch in 2006 while scouting for jaguar habitat, trying to track the origins of the jaguars that occasionally appeared in Arizona. Avila, a Mexico native, says that Robles “was already using phrases such as ‘ecological processes’ and ‘conservation in perpetuity,’ and I thought, ‘Who is this guy?’ Then he comes out with a folder containing a bunch of photos, of bobcats, mountain lions, black bear, deer and coati, and told me he had two or three remote cameras already.”

In February 2007, Robles let Avila’s group set up six more cameras on the ranch. (Eventually the total grew to 12.) The cameras have documented seven ocelots — the northernmost known breeding population — and two jaguars, as well as bobcats. Later that year, Robles signed an agreement with Sky Island Alliance in which he promised not to kill predators or poach wildlife on his land. In return, Sky Island agreed to promote the ranch — in the media, in the group’s writings and on its website — and to collaborate with Robles in monitoring wildlife and to support restoration activities, such as water pumping for wildlife. Avila and other Sky Island staffers became the ranch’s most enthusiastic U.S. advocates, leading more than 30 field trips and conducting wildlife tracking and restoration workshops. The group has also built rock dams along creeks to slow flows and encourage vegetation growth, and has helped conduct biological studies here.

Ornithologists, herpetologists, mammalogists, ecologists and other biologists from Mexico and the U.S. have come here to research many species, including the endangered Gila topminnow and Sonora chub, the lowland leopard frog, and the Tarahumara salamander (a population that Robles discovered). University of Sonora biology students visit to learn to use remote cameras and do other research. High school students and Boy Scouts from Sonora, along with a Border Studies group of students from Earlham College in Indiana, have done restoration work here, building at least 15 of the small rock dams that encourage wetlands.

Robles developed a simple website and Facebook page, but mostly relied on word of mouth to attract ecotourists and hunters. He spelled out his vision in a brochure filled with photos of wildlife and people in workshops. “We pursue to create an ecological paradise, but we are also committed with the community,” the brochure says. “We seek to be a leading example for the world’s conservation practices, instilling in people the ecological values to help them learn how to live in balance with nature, and set up the perfect environment for research projects. We aim to establish a sustainable model that protects biodiversity, supports other landowners, teaches and helps the community.”

For several years in the 2000s, Robles’ hunting and ecotourism business drew increasing numbers of customers. They stay in La Casona, or the big house, a brick-and-cement ranch compound built in the 1960s that can accommodate 15 people comfortably — and up to 35, if some are willing to sleep outdoors. Virtually all of his customers have come from the U.S.

Two hunters from the Phoenix, Ariz., area are regular customers, paying $4,500 each to bag Coues white-tailed deer. They say they were attracted by the ranch’s spectacular beauty as well as by its deer, which they describe as healthier than those on most Arizona lands. “There is a very important pride of ownership in this property — you can tell whenever you see Carlos and listen to him speak about his land and his dreams for the ranch,” says Joe Del Re of Chandler. Robles’ conservative harvest quota and grazing management allow many deer to reach trophy class, says the other hunter, Charles Kelly of Scottsdale.

Tom Wood of the Southeastern Arizona Bird Observatory says he’s taken birdwatchers from all over the country to Aribabi to glimpse gray hawks and green kingfishers — birds that are much rarer in the U.S. A single birdwatcher staying at Aribabi pays $89 for one night and about $350 a week, including meals; couples and larger groups pay less per person.

But starting around 2008, Robles says, his income from ecotourism and hunting plunged 60 percent. Customers from the U.S. are increasingly fearful of being caught in the cartel violence; according to Wood and hunters Kelly and Del Re, that’s a larger factor than the generally sagging economy. All three say they’ve seen no safety problems near Aribabi. But Wood, who has not led a birding trip to Aribabi in more than two years, says, “Until people feel comfortable traveling in Mexico again, it will be kind of hard to make a living in ecotourism.”

Three longtime birdwatching guides who work in Sonora and other parts of Mexico — Borderlands Tours and High Lonesome Tours, both based in Arizona, and Solipaso in Alamos, Sonora — say they’ve also seen a major dropoff in ecotourism due to fears of violence. Mexico has been a mainstay for 25 years for Borderlands owner Rick Taylor, but in 2011, for probably the first time, he didn’t run a Mexico tour, he says. He cancelled seven tours to Chiapas, Veracruz, Oaxaca and San Blas, among other places, after getting only a handful of inquiries.

Most of the cartel violence — the headline-making decapitations and machine-gun shootouts — occurs many miles away from Robles’ ranch, in cities hugging the border, especially Juárez (across the river from El Paso, Texas) and eastward. And most of the victims are cartel members, law enforcement or immigrants headed for the U.S. — an increasing sideline for the cartels. Even so, the average murder rates in Sonora and Chihuahua are higher than in Arizona, the Arizona Republic reported recently.

In February, the U.S. State Department issued the latest in a series of warnings to U.S. tourists, reporting that the cartels killed nearly 13,000 people in the first nine months of 2011 alone. “While most of those killed in narcotics-related violence have been members of (cartels), innocent persons have also been killed. The number of U.S. citizens reported to the Department of State as murdered in Mexico increased from 35 in 2007 to 120 in 2011. … U.S. citizens have fallen victim to … homicide, gun battles, kidnapping … Carjacking and highway robbery are serious problems in many parts of the border region and U.S. citizens have been murdered in such incidents. … In addition, local police have been implicated in some of these incidents.” Few of the 150,000 U.S. citizens who cross the border on an average day are targeted, but nevertheless, the State Department warned: “You should defer non-essential travel” in Chihuahua and parts of Sonora and Baja.

Warnings like that, and sensationalized U.S. news stories, have whipped up fears even in places in Mexico that are not gripped by violence. “Americans are scaredy-cats — now they’re worried that a ricocheting bullet from the border south of Texas might hit them 1,000 miles south of Tucson,” Taylor says. “Sure, a mass execution is a horrible thing. But who are the victims? They are El Salvadoran and Guatemalan immigrants (or cartel soldiers). We provide the market (for the cartels’ drugs and immigrant workers), we provide the weapons (guns from U.S. sellers), and we provide the media attention when drug cartels do anything awful.”

For Solipaso, fears of violence have reduced hotel reservations by 50 percent in the past two years and birdwatching by 25 percent, says Jennifer MacKay, who has run the business with her husband, David, for 12 years. “I get so many emails from (potential) visitors, asking, ‘Is it safe?’ ” says MacKay. “We have guests who travel all over with my husband and then come here for a couple of nights and find out it is totally fine and (the danger has been) blown out of proportion.”

But the risk of violence has also worried U.S. conservation groups that work in Sonora and Chihuahua. The Tucson-based Sonoran Institute pulled back for several years from a restoration project it had been working on along the Santa Cruz River in Sonora — about 20 miles from Rancho El Aribabi — after a former employee living there warned about the risks. Last fall, the Sonoran Institute resumed the project, this time in partnership with Sky Island Alliance, after the same person said it was safe “if you practice caution.” As the Sonoran Institute’s Emily Brott says: “Don’t drive at night. Don’t go alone.”

Staffers for five other U.S. groups working in Northwest Mexico say they haven’t cut back operations due to the violence. But they have to go through a lot more checkpoints on the roads now, as various Mexican lawmen search cars for guns and other evidence. And one of the groups, Defenders of Wildlife, has stopped taking donors on visits to sites in Northwest Mexico. A conservation rancher in Chihuahua says, “There was a murder near my ranch a few weeks ago. Just cartel-to-cartel, but I heard the gunshots. And then dead bodies were found about 15 miles from my ranch.” Farther south, a few Mexican environmentalists and government environmental officials have been kidnapped or murdered in the last two years.

“Definitely, conservation has been hard hit” by fear of the cartel violence, says Ernesto Enkerlin, who ran one of Mexico’s top conservation agencies, Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas, or CONANP (which manages federal conservation areas), from 2001 to 2010. Although many U.S. groups are hanging in there in Mexico, Enkerlin’s sense is that some groups and researchers “are now afraid” of traveling in Mexico, or “they’re concerned about liability and not letting their people come into Mexico” as much as they used to, or “they’re reluctant to invest in (Mexican) projects where bad things might happen.”

Lush riparian habitat on Rancho El Aribabi, which has been lauded by scientists and conservationists on both sides of the border.

Photo by Raechel Running

Mexico’s system of conservation relies a great deal on ranchers like Robles and other landowners, because there’s relatively little government land devoted to conservation. (See sidebar describing more ranches and Mexico’s system of conservation.) “There can be no conservation in Northwest Mexico if it doesn’t involve landowners,” says Enkerlin, who’s now with Monterrey Tech University. The conservation ranchers are doubly impacted as the cartel violence discourages some U.S. groups and results in “less income from hunting and ecotourism.” Ranchers like Robles “are exactly the kind of people we need more of,” Enkerlin says. “It’s really sad.”

In late 2010, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service nominated Robles to be part of a new binational jaguar recovery team. In early 2011, the Mexican agency CONANP formally recognized Robles’ ranch as a “protected natural area” — the country’s second-highest status for conserved land. The program allows Robles to keep that status even with cattle back on his land. It raises the profile of his conservation efforts, but probably won’t lead to much federal funding. “In theory, there are benefits,” Enkerlin says, “but things are happening much slower and with much less resources than we imagined” when the program was ramped up in 2007. And the federal designation of Robles’ ranch as an UMA, so he can manage deer and sell hunts, came with no funding, Robles says.

Robles says he needs $40,000 to $50,000 a year to maintain the ranch and keep it safe from intruders. He has applied for a grant from a different Mexican program that pays ranchers for providing ecosystem services, such as healthy watersheds, but has yet to receive a response. Enkerlin, who helped create that program in 2003, says it’s also very short of funds; it’s been increased to $80 million a year from $30 million in the first year, but “that’s not enough” spread across all the acreage of ranches and other private and communal land in Mexico. “The incentive is very small compared to the pressure” to run cattle and build subdivisions.

Mexican conservation groups tend to be smaller and have fewer resources than their U.S. counterparts. The key Mexican conservation groups active in Sonora and Chihuahua — ProNatura and Naturalia — say they aren’t able to help Robles. He keeps hoping to get direct financial support from Sky Island Alliance, but that group says it doesn’t provide subsidies for ranchers. Later this year, though, Sky Island Alliance will start a three-year restoration effort on Aribabi and four other Sonoran ranches, building more erosion-control structures and planting vegetation along creeks — an effort financed with a $189,000 grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, combined with $650,000 the group raised.

Sky Island staffers say they believe that, sooner or later, Robles will again remove the cattle from the land. “Carlos and his family are really amazing models — they’re rock stars in terms of conservation,” says Melanie Emerson, the group’s executive director. “It’s a tough, tough road that they’ve chosen, they’ve made personal sacrifices, and we applaud them.”

Robles even has plans to expand, by building more cabins for tourists and applying for more Mexican federal grants. He’s also begun making charcoal out of dead mesquite trees, for another trickle of income. And despite the financial hardship, he has continued to keep two key areas entirely cattle-free — the Río Cocóspera riparian area and Cañon de las Palomas, where jaguars have been photographed.

“The human race needs to see and do things differently, and show the new people that we can change the way of living,” Robles wrote in an email. Otherwise, he said, “the human race goes straight into a big hole with no way to return.”

This story was funded by contributions from High Country News readers and the High Country News Enterprise Journalism Fund.

Tony Davis is the environmental reporter for the Arizona Daily Star in Tucson. He’s written dozens of stories for HCN since the 1980s, on a range of topics including water, livestock grazing and mining. You can contact him at tdavis789@yahoo.com. Ray Ring, HCN senior editor, contributed to the story.